|

TRANSLATIONS

In the Mamari moon calendar 26 nights are indicated by a standardized glyph type oriented with the lighted side of the moon at left, e.g. as in Ca7-2 (Kokore tahi):

I have counted also the glyphs which incorporate the standard glyph type, viz.:

Two glyphs at the beginning of the calendar and two in the middle have non-standard shapes:

I guess Ca7-23 and Ca7-24 should be added to those 26 and that the sum (28) then represents the number of nights when the moon is illuminated by the sun. We should notice that this pattern (left side illuminated) does not change in spite of the reversal at full moon. The standard glyph type seems to have lost contact with its origin and become a symbol instead of a translation of observation into image. In the Tahua year calendar, on the other hand, the reversal of sun at midsummer is captured in image form and the 'month' glyphs seem to be non-standard, except possibly those 4 preceding midsummer. The after midsummer (en face) glyph Aa1-10 has an elbow ornament in form of an after full moon sickle (as observed from a point south of the equator):

The elbow signifies a point of turnover (change) and we should probably understand the elbow ornament in Aa1-10 as 'past maximum'. The nights Ohua and Otua have 'counters' referring to the sun respectively the moon:

There are 6 'counters' on Ca7-14 and 15 on Ca7-15. The 6 marks are divided into two groups with 3 in each. Not only are the groups located on opposite sides of the 'fruit' but they are also located on opposite sides vertically seen. The 'fruit' thereby may become a symbol for the year, with - it seems - 4 quarters of different qualities. 15 * 28 = 420. The implication might be that Ca7-16 indicates full moon, i.e. that 15 full moons are needed to reach 420 nigths (at which point the sun has completed his 14 cycles). The 'foot' of Ca7-15 is shown without 'toes', which probably means that after 420 nights the grand cycle is ended (cut off, koti). The difference between 420 and 360 nights possibly is indicated by the 'tail' at the bottom of Ca7-14. Only by returning to the 'axioms' (here the moon calendar), and investigating if more 'light' now is falling on the glyphs than earlier - due to discoveries and ideas accumulated by the efforts to understand other parts of the rongorongo texts - can a secure foothold be created in translating the texts. Although only such internal evidence may be permitted as 'proof', the myths and stories from Easter Island (and Polynesia and the rest of the world) provide ideas stimulating further efforts. Take for example the 3 Pure (shells with sounds of the sea?) sent out to fetch the 'image' of king Oto Uta: "Up to now, the only known version of the tradition of the broken stone figure was the one of Arturo Teao. The version by Jóse Fati (Felbermayer 1971:19-20) largely agrees with it, except that in this version the king commands six servants to go back to 'Maori'. My translation is from the Rapanui texts recorded by Englert: When the king had taken up residence in Anakena, in Hare Tupa Tuu, he said to the two men, 'Return to Hiva, to the (home)land, to the stone figure (moai maea) and bring the figure back. It was left out in the bay. Be careful when you get to the bay that the companion (mahaki), the Tautó, the king, is not broken!' Two men sailed in the canoe. There were no waves; the water was not turbulent (pari); there was no wind. The men sailed and landed in Hiva. When they had landed there, they saw that the figure (moai) was standing upright (maroa) out in the bay. They broke the neck of the figure, of Tautó. At that, the waves broke, the wind blew, the rain fell, the thunder rolled, and a meteorite fell on this land. Hotu Matua knew what had happened and lamented, 'Ah - broken is the neck of the figure, of the Tautó, of the king. You were not careful with the companion (mahaki).' (He) called to the servants (tangata vere taueve): 'Go down and see the companion, who was brought on land, on the beach, the beach of Hiro Moko.' The men went, arrived, and saw that (the figure) had landed on shore. They picked up the figure, the figure of Tautó. There was only a face (aringa) and a neck (ngao) (i.e., only the head of the figure was left). They picked it up, went to the king, and handed (the fragment) over to the king, to Hotu Matua. The king wept because the body (hakari), the legs (vae), and the arms (rima) had been (left) in Hiva, in the (home)land. The king lamented, '(So) this is how you came from Hiva, from the land where there is an abundance of food, where the lips ooze with the waste (of the abundant food) (kainga kai nui ngutu oone)!' (TP:44-45). This version basically agrees with the theme of the one in Ms. E but has fewer details. The two men the king commissions to go back to the homeland have no names, the king's lament is missing, and the name of the stone figure is 'Tautó', a form not used anywhere else. Details mentioned in this version but not in Ms. E include the calm state of the elements during the trio's voyage to Hiva, the landing of the fragment in 'Hiro Moko', the birthplace of the king's successor, the precise description of what was left of the stone figure, and another metaphor for the homeland." (Barthel 2) Names give us clues:

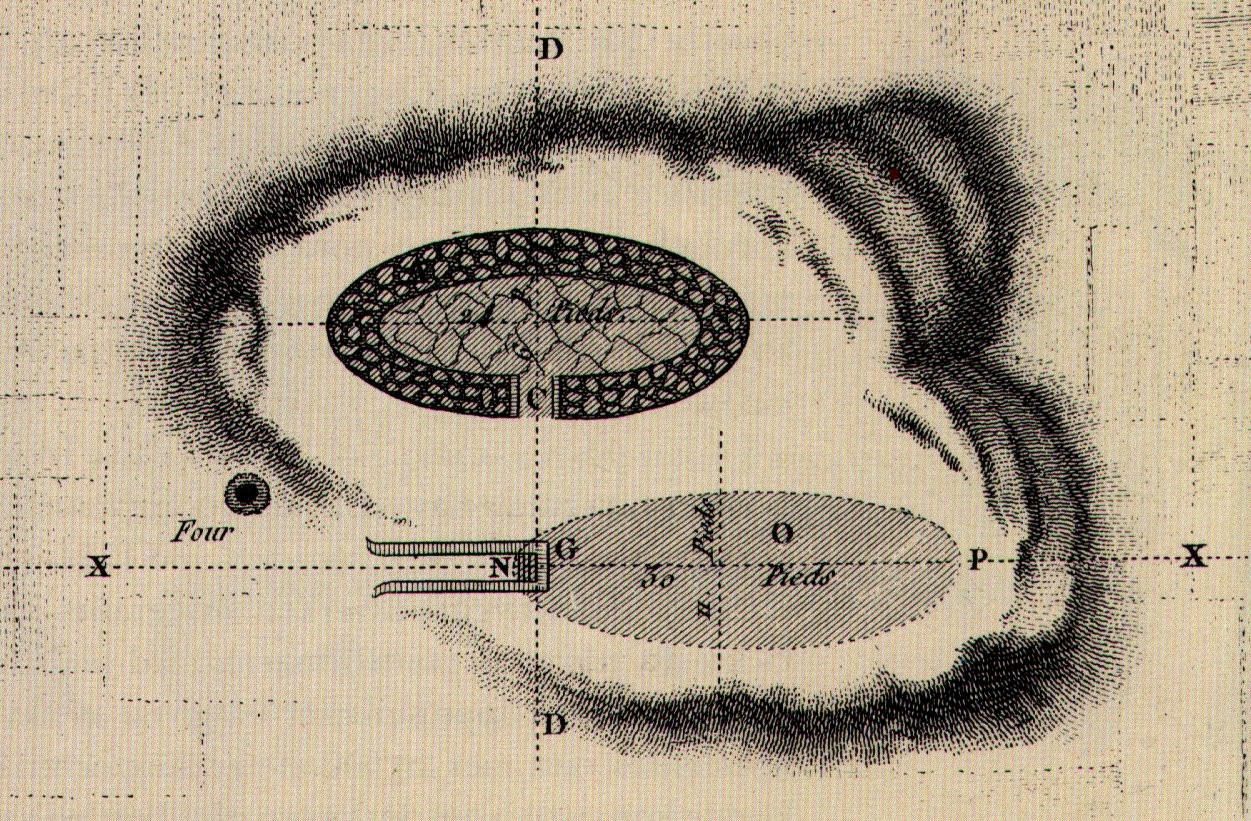

Tautó makes me think about a rock (tau) in the water marking the border between one (watery) season and the next, but that is because of the example i uto to te hau. Nothing in the word to as such indicates water, rather the opposite because to may mean the rise of the sun during a.m. (i.e. after he has 'gone ashore'). And then we cannot be sure that tó and to are the same words. However, the examples in Vanaga have proven valuable because they present associations engendered by the key words. Therefore I guess that to has to do with water and that there is a ribbon (hau) - presumably a mark of end (as in maro) - and that there is something afloat (uto) on the water. A weak 'proof' indeed, but the pattern is there. Nets belong to cardinal points. Uto sounds similar to uta and uto is sticking up in the sea while uta is up on the land. And the association to Oto Ota is near: Cfr U-ta and U-to with O-to and U-ta. A wordplay maybe, but if so, then Oto is sticking up in the sea and the idea is to get him up on land as Uta. In Hare Tupa Tuu (at Anakena) Hotua Matu'a had his residence at the time of the incident with the stone statue. The tupa buildings were compared to the South American chullpa by Schumacher: 'Compare also the type of structure, mainly in the Lake Titicaca basin area, called chullpa and Easter Island's tupa, both apparently built as 'adoratorios', in which mummies, skeletons, and skulls were displayed and worshipped … where tupa would be the expected Polynesian revaluation of chullpa.' What intrigues me is the fact that (on Easter Island) there were two parallel structures, one above ground and one below:

The entrance to the above ground hare is 'midships', while the underground is reached through the tunnel at the short end. '…to enter a war canoe from either the stern or the prow was equivalent to a 'change of state or death'. Instead, the warrior had to cross the threshold of the side-strakes as a ritual entry into the body of his ancestor as represented by the canoe. The hull of the canoe was regarded as the backbone of their chief. In laments for dead chiefs, the deceased are often compared to broken canoes awash in the surf.' (Starzecka) The name Hare Tupa Tuu therefore suggests the abode of the dead.

To bring in on a stretcher a dead or wounded person (tupatupa) reminds me about Kuukuu (sun), struck by the 'turtle' (hônu) at winter solstice: '... They put the injured Kuukuu on a stretcher and carried him inland. They prepared a soft bed for him in the cave and let him rest there. They stayed there, rested, and lamented the severely injured Kuukuu. Kuukuu said, 'Promise me, my friends, that you will not abandon me!' They all replied, 'We could never abandon you! ...' Presumably we should interpret a hare tupa as a kind of cave. The word Tu'u (in Hare Tupa Tuu) has a complex meaning, but surely we must translate the word into 'to stand erect' (like a god?), but also 'to arrive' (in time/space), i.e. I guess that tu'u is a godlike post standing in the water to mark the point of arrival:

The water is suggested from various cues, e.g. tuu mai te vaka (to hail the canoe). Tu'u aro, northwest and west side of the island, indicates that the cycle of the year has arrived (tu'u) at late autumn (fall). The dark 'half' of the year is 'underground', in the land of the spirits (dead). Being underground is equivalent to be 'in the depth of the sea': "... the canoe adventure of two Cherokees at the mouth of Suck Creek. One of them was seized by a fish, and never seen again. The other was taken round and round to the very lowest center of the whirlpool, when another circle caught him and bore him outward. He told afterwards that when he reached the narrowest circle of the maelstroem the water seemed to open below and he could look down as through the roof beam of a house, and there on the bottom of the river he had seen a great company, who looked up and beckoned to him to join them, but as they put up their hands to seize him the swift current caught him and took him out of their reach. It is almost as if the Cherokees have retained the better memory, when they talk of foreign regions, inhabited by 'a great company' - which might equally well be the dead, or giants with their dogs - there, where in 'the narrowest circle of the maelstroem the water seemed to open below ..." (Hamlet's Mill) The spirit world is furthermore suggested by the word pure: "The transportation of the stone figure from Hiva is not a historical authentic voyage because all the protagonists are spirits. Kuihi and Kuaha, the guardian spirits of the immigrant king, who are at his side at crucial moments (Oroi conflict, hour of death), transport the (deliberately severed) head of the stone figure to the beach of the royal residence. Kui was - we remember - the man who drowned (i.e. he is a spirit now): 'There is a couple residing in one place named Kui and Fakataka. After the couple stay together for a while Fakataka is pregnant. So they go away because they wish to go to another place - they go. The canoe goes and goes, the wind roars, the sea churns, the canoe sinks. Kui expires while Fakataka swims ...' Another kui was Kuikava (also dead now): '... He goes over to where some work is being done by a father and son. Likāvaka is the name of the father - a canoe-builder, while his son is Kuikava. Taetagaloa goes right over there and steps forward to the stern of the canoe saying - his words are these: 'The canoe is crooked.' (kalo ki ama) Instantly Likāvaka is enraged at the words of the child. Likāvaka says: 'Who the hell are you to come and tell me that the canoe is crooked?' Taetagaloa replies: 'Come and stand over here and see that the canoe is crooked.' Likāvaka goes over and stands right at the place Taetagaloa told him to at the stern of the canoe. Looking forward, Taetagaloa is right, the canoe is crooked. He slices through all the lashings of the canoe to straighten the timbers. He realigns the timbers. First he must again position the supports, then place the timbers correctly in them, but Kuikava the son of Likāvaka goes over and stands upon one support. His father Likāvaka rushes right over and strikes his son Kuikava with his adze. Thus Kuikava dies ...'

'At Mangaia the spirits of those who ignobly died 'on a pillow' wandered about disconsolately over the rocks near the margin of the sea until the day appointed by their leader comes (once a year). Many months might elapse ere the projected departures of the ghost took place. This weary interval was spent in dances and revisiting their former homes, where the living dwell affectionately remembered by the dead. At night fall they would wander amongst the trees and plantations nearest to these dwellings, sometimes venturing to peep inside. As a rule these ghosts were well disposed towards their own living relatives; but often became vindictive if a pet child was ill-treated by a stepmother or other relatives etc ...' However, Ku-ihi (not Kui-hi) and Ku-aha (not Ku-iha) is another interpretation:

From there, a servant of the king, who is mentioned by name [Moa Kehu - the helping 'bird' (moa) for the 'sun' (Hotu Matua) who has sunk below (kehu) the horizon], carries the fragment of Oto Uta to Hotu Matua's house. If the last segment of the tradition is to be taken literally, the stone ancestor's head did not weigh more than what a man can carry. The three 'fellows' (kope), commissioned by the king to bring the figure of Oto Uta unharmed from Hiva, all have names of spirits (akuaku) that live in the sea near Vai Hū and Hanga Tee on the southern shore. Hiva is the land of the spirits: 'During my field work, questions about Taana yielded the following answer: Once he ruled a land called 'Hiva' or 'Ovakevake', where all spirits (akuaku) have their home. Through the power of his mana he learned of the location of Easter Island and sent his three sons [the 'handsome youths of Te Taanga, who are standing in the water', i.e. the three islets off the southwest point of Easter Island] across the sea to the island ...'

"That there is a whirlpool in the sky is well known; it is most probably the essential one, and it is precisely placed. It is a group of stars so named (zalos) at the foot of Orion, close to Rigel (beta Orionis, Rigel being the Arabic word for 'foot'), the degree of which was called 'death', according to Hermes Trismegistos - Vocattur mors. W. Gundel, Neue Astrologische Texte des Hermes Trismegistos (1936), pp. 196f., 216f. - whereas the Maori claim outright that Rigel marked the way to Hades (Castor indicating the primordial homeland) ..." (Hamlet's Mill) The 'foot' (Rigel) possibly is indicated in the X-area by the leg (vae) in Aa1-15:

And maybe the three open limbs of the moa at right indicate the spirit state of nonsubstantiality? Three spirits - like strings or filaments (kope - cfr the ribbon in the float, i uto to te hau):

My informants (Laura Hill and Vincente Pons) gave me the names of four spirits, 'Pure Henguingui', 'Pure Ki', 'Pure O' and 'Pure Vanangananga', in connection with the traditional instruction to speak softly while gathering mussles at night on the beach (of the same coastal stretch). The instruction can be explained in the following way: pure means both 'cowrie' (PPN. *pule 'cowrie') and 'prayer' - in the Easter Island script both are represented by Rongorongo 25 - while the qualifying additions refer to various ways of speaking. Barthel's number 25 corresponds to my GD25, i.e.:

I have not yet found any evidence affirming Barthel's interpretation of GD25 as 'prayer' or 'cowrie'. But I have seen that Metoro very often used pure(ga) as an explanation for GD25 glyphs (or once in a while hare pure - which I for the moment guess means 'spirit house' or something similar). As in the underground mirror cave of an above ground built tulpa there seems to be no other opening in GD25 than at the short ends (though here there are two such - which I guess may be understood as the two solstices - when time stands still holding its breath and anything might happen). Aa7-3 seems to have a sign of GD25, somewhat similar to the noon glyph Aa1-26:

And the 'tail' of hakaturu (right center in Aa1-26) has vanished like a ghost. RAP. henguingui is synonymous with MGV. henguingui 'to whisper, to speak low' and goes back to west Polynesian forms (SAM. fenguingui 'to talk in a low tone'; UVE. fegui 'murmurer'). In many of the Polynesian languages , ki is the spoken word; in some few, ki refers to the process of thinking; (MGV., MAO., HAW.) and in some instances, it indicates special noises (MQS. ki 'to whistle with two fingers'; SAM. 'i 'to call like a bird'; TON. ki 'to squeal'). Generally, o is the affirmative answer to the caller, while vanangananga indicates repeated speaking. The four spirits represents, on one hand, the sound scale of empty conch shells and, on the other hand, a classification of types of prayers ..." (Barthel 2) Why are there only 3 Pure emitted by Hotu Matua? Shouldn't it be an even number? As O, Ki, and Vanangananga were three of a quartet we miss Pure Henguingui. Maybe it has something to do with the 3 X-time glyphs?

There are 4 ghostly beams of light in Aa1-13, but there are only 3 'fruits' (hua, offspring) as 'passengers' in the canoe of Aa1-14. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||